Epigenetic Topographies

Welcome to Wandering Grace. I share essays exploring the themes of place and (be)longing 1-2 times a month that follow the stops of my 2023 Migration Tour, and sometimes bonus snapshots from the road. Read more about the project here. See an archived list of essays in-order here.

Last time, I wrote about moving for love. This time, I write about epigenetic topographies.

Thank you for your support of this project. Please forward this to someone who might resonate with its themes, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription if this writing is meaningful to you.

This essay is in direct conversation with these three previous Wandering Grace essays, so I will link them here for reference and for new readers. (I dare to dream that this series might someday become a book of essays, wherein these connections and weaves make sense in braided form over the course of 200 pages that you hold in your hand…)

Into the silences

Welcome to Wandering Grace. I will be sharing essays exploring the themes of place and (be)longing every other Thursday, and bonus snapshots from the road on alternating Sundays. Read more about the project. Last week’s bonus: photo essays on the layer cake of time

Not NOT intact

Welcome to Wandering Grace. I will be sharing essays exploring the themes of place and (be)longing every other Thursday, and sometimes bonus snapshots from the road on the weeks in-between. Read more about the project here. See an archived list of essays

A felt sense of home

Welcome to Wandering Grace, especially if you are a newer subscriber! We are only 6 people away from 100 subscribers! Please help me grow by sharing with friends and kindred spirits. I write essays exploring the themes of place and (be)longing 1-2 times a month, and sometimes bonus snapshots from the road. Read more

It’s June 2023. I’m on my Migration Tour. I meet my friend Amanda for a hike at Deukmejian Wilderness Park at her suggestion. I laugh that she happens to have her mini silver ACA water bottle with her — unplanned and unironically. I regret that I lost mine in the years since! That artist residency themed around constraints and labyrinths at Atlantic Center for the Arts is where we met years ago in 2018. We take a selfie to text to our cohort’s email thread.

Clouds fog up the hillsides on this grey June gloom day. There is a familiarity to the highways wending their way through the mountains on either side that feels bigger than ‘I used to live here’.

It occurs to me that Vietnam might include similar terrain. Having never been there myself, I’ve never given much thought to the topology of the country my parents are from. A flash of: faux newsreel footage in the movies of mountainous jungles as seen from the open door of a helicopter, an American soldier straddling a gun with their legs dangling down in the open air.

I remember that the country abuts the ocean along it’s vertical axis. Is that why my intuitive birds’ eye view map of Migration Tour stops was all mountaintops and oceanside stops?

***

It’s over a year later, September 2024. I have moved to LA, and I’m at Amanda’s lunchtime birthday party at a brewery in Atwater Village. Her friends exchange theater industry tea about a one-woman show called Dragon Lady that Amanda recently reviewed; an auntie posted on social media that Amanda’s review is the only one that’s not ‘culturally tone-deaf’. I have tickets to see a 3 pm showing that same day.

Dragon Lady is part one of a trilogy telling the stories of three generations of Filipino women, mom and daughter, mom and daughter, grandma and granddaughter, weaving together their often-contradictory perspectives of each other’s stories in a way that feels honest to the living stories of intergenerational immigrant families navigating shifting contexts of era and place.

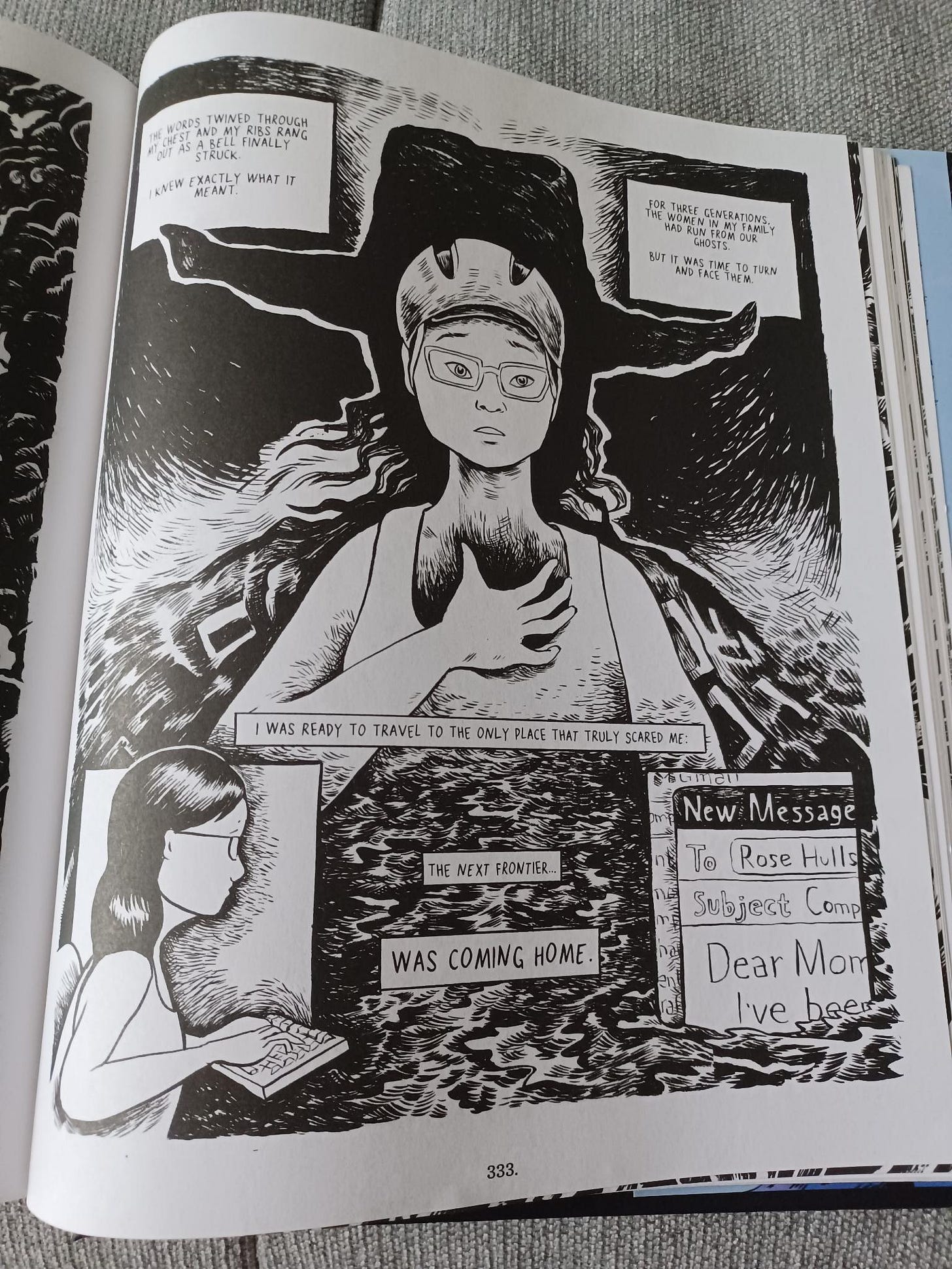

What I leave the theater with: Sara Porkalob’s divine voice, and her grandma Maria’s stories, and Sara’s deft ability to embody and portray dozens of distinct characters, the lift of laughter, and the way this story sits alongside other intergenerational braids I’ve been encountering: Tessa Hulls’ graphic memoir Feeding Ghosts which intricately braids her mom’s and her grandma’s and her own stories; the fictional story of three generations of Chinese-American seeking in Rachel Khong’s Real Americans, separated into three distinct sections starting with mom, moving onto son, then returning in time to grandma.

I try to search for Amanda’s review afterward. I can’t find it on the first couple pages of results. I’m looking for resonance and context and voices to ‘watch the show with’, similar to how I look up takes and recaps after seeing a particularly layered season of prestige TV…so I find myself only half-skimming other reviews. I can’t quite stomach the potential minefield of ‘tone-deaf’ reviews.

One reviewer’s take particularly rankles: “What follows are scenes out of a movie melodrama — helpless poverty, horrific exploitation, routine brushes with violence and near-death escapes — performed under the guise of a karaoke cabaret…One of the issues is that the tale being spun raises more plot questions than can be answered in the allotted time. Details and consequences are breezed over or ignored entirely, making ‘Dragon Lady’ seem sketchy in places.”

The (white) reviewer wants coherence from the immigrant trauma.1 I cringe from the familiarity of this demand and its hand-in-hand erasure.

When I finally find it, Amanda’s review offers grace and (re)contextualizes the gifts of the mysteries left alive in the storyline.

“While some storylines are never resolved, such as the origins of Maria Jr.’s birth (Was she truly kidnapped by a gangster when she was a baby?), these incongruencies actually reflect a diasporic and homeland Filipino experience where birth stories, parental ties, and family relationships can be obscured or mythologized in order to protect secrets or hide grief. Plus, the unresolved stories create a great cliffhanger and setup for the rest of the cycle, Dragon Mama and Dragon Baby (the latter currently under development).”

***

I still can’t quite name the mechanisms around how this demand for legibility-to-whiteness is a form of gaslighting that contributes to erasure, but I know that it’s real because I’m still recovering the voice and sure-sense-of-self that I lost in Oregon amidst this same assimilationist demand (internal + external) that we ‘make narrative sense’ to the colonialist project’s dominant storyline.

My sense of self and voice have always been a mosaic, a modge podge, a beautiful patchwork quilt…and yet my belief in the beauty of that collage became subsumed and drowned to meet someone else’s need for logical coherence, motivated by an unshakeable need to belong.

***

“why some people be mad at me sometimes” by lucille clifton

they ask me to remember

but they want me to remember

their memories

and i keep on remembering

mine

***2

It’s October 2024 as I write this, and there is a whole drafted-but-unwritten essay that is a response to the white reviewer’s review, a defense of the holiness of a holey narrative. Maybe I’d quote a white lady writer Mary Karr on the inherent patchwork nature of memoir to give myself ammunition and to lend my argument weight.

The me of 2018 did write such a rebuttal at the artist residency where I first met Amanda.

The me of 2022 in Oregon kept trying and failing to write again and again the why’s and wherefore’s of what was eradicating my voice and thus making it impossible to write.

The me of 2024 is choosing not to write that essay. To do instead, what Toni Morrison counsels:

“I urge you to be careful. For there is a deadly prison: the prison that is erected when one spends one’s life fighting phantoms, concentrating on myths, and explaining over and over to the conqueror your language, your lifestyle, your history, your habits. And you don’t have to do it anymore.

You can go ahead and talk straight to me.”

***

a poem by patrizia cavalli in translation

To get out of prison do you really need

to know what wood the door is made of,

the allow of the bars, the precise hue

of the walls? Becoming so expert, you might

grow too fond of the place. If you really do

want out, don’t wait so long, leave now,

maybe use your voice, become a song.

***3

It’s February 2024, and I am living in limbo at a sublet in San Francisco. I am taking a weekly class from the School for Poetic Computation called “Relational Reconstructions” that starts at 6 am Pacific Time, 9 am Eastern Time, and 9 pm Taiwan Time.

I joke in the application that I’ll be taking this class in a fugue state between dreaming and waking, as I am not an early bird — not even aspirationally. Some Saturdays, I log online still lying down in bed, my bedside lamp glowing orange behind me, camera off. I catnap through the activity to make our own homemade wheatpaste from smashed cooked rice.

In class, we work with family photos — to (re)create archival memories, to turn 2D static snapshots into 3D artistic living diaroma.

The act of recreation is an act of research and reverie, of re-discovery and re-memory. Of re-embodiment and re-existencia. Offerings to the ancestors similar to those of fresh fruit on altars, which we then enjoy or eat ourselves after they have feasted first. Saidiya Hartman’s critical fabulation.

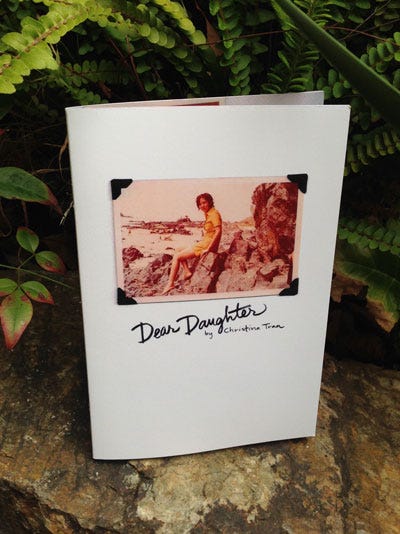

I work with this photo of my mom as a teenager posed on the beach which was the cover of my Dear Daughter zine, simply because it is already scanned and easily accessible on my harddrive at 7 am in the morning before the sun has risen on the Panhandle.

At the end of one class when we’ve been working on our memory spaces, I’ve moved from the bed to the desk, and drawn open my curtains as morning sunlight changes the sensation of my room.

In order to extend the photo beyond its edges to create a digital diorama and to fill in more sensorial details, I search for popular beaches in Southern Vietnam, looking through tourist reviews and uploaded photos, combing for rocky ones with huge grey boulders. I’m more awake and leaning forward towards the screen, steeped in the dark quiet of Mozilla Hubs, cozy in familial warmth as my mom gazes at me from her perch, flowing as I follow the connect-the-dots energy along the edges of mystery.

I decide to look up the beaches from the travel listicle one-by-one on Google Streetview to cross-compare.

This one

these fisher boats

I’m delighted to find a feature where you can click arrows to view photos taken in the same spot during different years, to go backward and forward in time. Someone’s posted a 360º photosphere of the coastline.

When I open Bãi Đá Nhảy up on maps, I gasp aloud to myself, “holy shit,”

I know this shoreline.

I saw it in May 2023 in Southern California near a Friendship Bell, where I recognized it as a feeling of home before I knew what I was looking at.

I’ve been calling it epigenetic topography — a reminder that we not only inherit the traumas, but also the resilience. We also inherit: felt sense of home, wisdom traditions in our bones, maps back to ourselves, clues to find our way, contextualized in space, reconstellated into a weave of belonging.4

Dancing Rock Beach.

The teachers from Relational Reconstructions Jeff and Dri ask: what is an encoded message that your ancestors left for you to find?

the smell of incense

the sound of a sewing machine

the swing of a hammer in your dominant hand

the taste of mango on a hot summer’s day

cut fruit and noodle soup

a cliff looking north where sand meets sea

this hike and this humidity with this friend who works in theatre and translation whom you met at an artist residency

a residency whose humidity and multicultural cohort reawakens a lust which you hadn’t realized had been missing in Oregon.

***

There is a felt difference between treating history and family stories and archives as inert objects to be studied and figured out and consumed vs. something we are in relationship to as living breathing stewards of lineage — to honor and to embody and to shape and to (re)create and to carry on and to pass along to those who deserve and respect the gifts we have been entrusted to bestow.

***

Saturday morning classtime. The sun has risen over the Panhandle and over my dreams. On my computer, and in my collaged photosphere, I intentionally collapse the layer cake of time by filling in the diaroma of my mom at the beach in 越南 in the 1970s with photos from my own migration tour from the 2020s — lava rock boulders and flourescent moss from Oregon beaches, curving ocean shoreline captures on top of a cliff looking north from somewhere between Los Angeles and San Diego, somewhere between the stolen homes of the Tongva people and the Kumeyaay.

Sara Porkalob’s show is also a layer cake of time, containing at least three generations of powerful femme stories — contradictory, patchwork, paradoxical, carnal, reaching, ever-reaching towards love and connection. Grandma Maria laces her fingers together — connection instead of distance, the distance between her daughter and herself, a distance she can’t bridge on her own, without telling her stories to her granddaughter in the hopes that she might help Sara’s mom / Maria’s daughter understand.

In her graphic memoir Feeding Ghosts, Tessa Hulls quotes Chinua Achebe who says, “Every generation must recognize and embrace the task it is peculiarly designed by history and by providence to perform.”

For whatever reason, my generation of second- or third-gen Asian American kids in this era, are drawn to healing work, to archival work, to storytelling work, to bridge generations, to sew together patchwork, to find ourselves decolonizing amidst the smells and sounds and embrace of our ancestors and their lineages — our lineages once again.

In the last act of Rachel Khong’s novel Real Americans, a grandma laments that her storied confessions to her grandson can’t bridge the gap to mend the wounds between herself and her daughter. And then the book ends with, “my daughter walks into the room.”

Porkalob’s show ends with her grandmother’s picture projected large on the screen behind her. Sara tells us that in past productions, before she passed away, grandma Maria herself would come onstage to sing the Filipino standard “Dahil Sa’yo.” Someone in the audience to my right gasps loudly as Sara starts singing the familiar lullaby.

I hope Sara hears it from onstage. A connection point across the divide of the darkened theater that trains us to keep our comfortable distance between audience and performer5 — ready to critique, judge, dismiss, or consume something as a piece of media.

At the end of the show, Sara Porkalob dries her tears after a standing ovation and tells everyone to sit back down for a few moments. She jokes that she used to end the show by going straight back to her dressing room and crying by herself, but decided that that ultimately wasn’t good for her mental health. Instead she introduces and thanks her band (who are playing a show this week in LA — we should go, she’ll be there!), shares a few more words of banter with us, and points us toward the merch she’s collaborated with her family on making, whose proceeds will benefit the Los Angeles Food Bank and API Chaya.

In breaking the spell of the fourth wall of the entertainer-and-audience relationship, it’s a small gesture to try and re-situate herself into a web of community, to try and re-contextualize past-trauma stories into present-day organizing around poverty, hunger, and human trafficking.

It’s not quite enough to shift us audience members out of our role as consumers-of-story, since the only additional path for us is to then become consumers-of-merch. But maybe that’s more on us than on her…

When: really, instead, and of course, it is an honor to hear someone’s family stories, to bear witness to a fellow creative’s process and processing, to be together in the mess of emotions that spring up in the wake of disconnection, to share in the irrepressible human desire to connect and reconnect and connect and reconnect.

Fingers laced together.

Stitching patchwork across time.

…without having to zoom out to understand and acknowledge and reckon with the contexts of imperialism and colonialism that often lead to that very trauma. To be fair, the show Dragon Lady also only nods to this herself, and it might be one of my few critiques. On my way to the show, I listened to Episode 121 of the Vibe Check podcast about the (mis)framing and (de)contextualization of the racist narrative against Haitian immigrants in Ohio, when they were invited in the first place.

gratitude to ames for sharing the lucille clifton poem in S.A. group

gratitude to deepa, kendra, and tanesia for sharing the patrizia cavalli poem in emerging community

I’m going to keep footnoting and pointing people to this Leah Manaema Avene post and also this one about re-constellating to belonging as a way to be in decolonizing solidarity instead of extractive colonialist patterns.

hello, do you want to geek out about infrastructure and ontological design? The Design Studio for Social Intervention put out a book about how [Ideas], [Arrangements], and [Effects] shape our world — and how we mis-focus on changing people’s ideas/beliefs about the world without realizing how much we are shaped by the physical arrangements that shape our behavior and beliefs of ‘how things should be’…something that I’ve been trying to name for years around “In Visibility” and “Inclusion”.