Welcome to Wandering Grace. I will be sharing essays exploring the themes of place and (be)longing every other Thursday, and bonus snapshots from the road on alternating Sundays. Read more about the project. Last week’s bonus: photo essays on the layer cake of time from the Oregon coast.

On April 8th, I hitch a ride south from Corvallis, Oregon to San Francisco, California.

In March, I had taken my friend Jen out for cupcakes to celebrate her “third year anniversary of being a full-time independent artist, designer and teaching artist.” I was telling her about my Healing Pilgrimage, and she mentioned that she would be driving down to the Bay Area for her sister’s birthday. She offered me a ride.1

We start the day off early. I catch a ride from Albany into Corvallis with my housemate Albert, who has to get into town early for a shift at the bakery. Jen and Rick meet us at the bakery with coffee in hand, but Wild Yeast isn’t open yet, so they don’t get breakfast.

Everyone’s quiet and still waking up as we pile into their SUV and take off on I-5 South.

Into the silence, Jen puts on the podcast Levar Burton Reads. In the back seat, I drift in and out of sleep to the voice of Burton reading a 1953 short story written by Kurt Vonnegut called “D.P.” about an orphaned boy in a small German village during World War II.2

The protagonist is “a lone, blue-eyed colored boy, six years old” who the locals have nicknamed Joe after heavyweight champ Joe Louis. One day, a villager teases Joe that his father is among the American soldiers who have just arrived in town. That night, Joe sneaks out to meet his “Papa,” a Black Sargeant whose battalion are at first amused and then heartbrokenly perplexed about what to do with this German-speaking brown-skinned kid craving kinship and belonging. Growing up, Joe had never seen anyone who looked like him, and he clings to the Sargeant — first physically to his leg, then fantastically to the idea of him in his mind.

***

I didn’t have Joe’s experience as a kid. I had grown up in multiracial Alief in Houston where the schools were “majority-minority.” But now…I think I may have experienced some of this cognitive distortion and cultural loneliness as an adult in Oregon.

Navigating race in America looks differently in different regions of this stolen land. When I moved, I knew that Corvallis, Oregon on unceded Kalapuya territory in the “Mid-Willamette Valley” was smaller and whiter than any place I had previously lived. But I couldn’t have prepared myself for the embodied experience of it. I didn’t realize how deeply disruptive the homogeneity would be to my body, my emotional wellbeing, and my sense of self.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie talks about “the danger of a single story,” and I chafe at characterizing my experiences in any way that reinforces the stereotype of “the only [minority] kid in school” as the predominant story of what it means to be a person of color in America. But there is something intriguing about what it means to encounter tokenization as an adult. And there is something humbling about feeling the full force of its oppressive effects despite, well, being a full-grown woman.

On one hand, my body relaxed into the slower pace of a smaller town and reveled in the deep greenness of the conifered hills and oak savannahs, the results of long rainy winters. On another hand, these landscapes also came with the kind of homogenous whiteness that pressures assimilation. Even if that assimilation was toward a palatable version of whiteness (progressive, liberal, hippie, middle class), it was the assumed default of a majority as normal that slowly boxed me in, suffocated me.

I was naïve about my abilities to resist the subtle forces that erase or invisibilize or shrink. The truth is I hadn’t built up resiliencies against assimilationist strands of racism3 because I had developed a different set of armor as a kid.

It would take me meandering years and years to be able to start to pinpoint and name this unease.

One of the hardest parts (still) is that almost no one talks about this racial/cultural dynamic of living in the Pacific Northwest.

Or to be more specific, there are two dimensions on a pole that I end up falling into (or trying to resist falling into) in discussions.

One end: Most of my small talk with people outside of Oregon about Oregon includes “it’s so beautiful” and “no, I don’t live in Portland, I live in Corvallis/Albany.”4 But it’s hard to talk about how I feel living here without reducing it to “it’s too white in Oregon”, which is too simplistic of a ‘single story.’ Saying Oregon is “too white” invisibilizes all the people of color who call this place home and flattens the diversity of bodies that already exists here. It also bypasses the history of racist genocide, exclusionary policy, and oppressive tactics that have created and reinforced the predominate whiteness of this place.5 But mostly we don’t talk about the discomforts of race at all because it’s presumed that Oregon is such a great place to live.

Another end: A lot of my conversations with people of color who live in Oregon about Oregon include some grousing about white people. These become BIPOC-ful spaces that still end up centering whiteness.6 These spaces are release valves for the silences we experience in other predominately-white parts of our lives (whether due to patterning, deference, and/or choice). We bond over shared oppressions, that someone else gets it, gets us.

A friend Eddie once called these old stuck stories ‘the stale taste of the familiar’.

I wanted more. I was sick (am sick) of centering whiteness.

***

From a journal entry on March 16, 2023:

When you are able to decenter whiteness, it is no longer gravity. It loses its power, its weight. Free dom.

Just transport me straight to incense and noise.

The spaces cocreated and coheld [by friends] which are so joyful.

I don’t want to be a BIPOC. I just want to be me.

***

Reasons for silence (an incomplete list)

I don’t have the words yet.

I don’t have the right words — the perfect words, the words backed up by links and evidence and research…and translated into something that the ‘white soma’7 can process and understand as legitimate.

I don’t have it in me to defend something that would feel devastating for me if you don’t believe my lived experience in the first place.

I don’t want to reinforce the ‘single story’ or stereotypes.

I’m tired.

If I say something, I’ll have to either educate or comfort, and I don’t have it in me to do that right now.

I’m choosing not to right now.

I’m afraid of conflict.

I’m unsure.

I’m still processing my own complicity and responsibilities in all of this.

I’ve learned to put the comfort of [the group / of this white woman / of my boss / of everyone else] ahead of my own needs.8

I have a right to opacity and privacy.9

I like being illegible, subversive, fugitive, confusing.10

I don’t want to.

I’m embarrassed.

I don’t trust this person to hold the complexities or nuances of what I want to share.

I’m enjoying this silence.

I resent needing to be the one to point out these obvious things.

I’m tired of doing this labor.

I’m burnt out from doing this labor.

I just want to write/talk about anything else that lights me up instead.

This is not my work.

This is my work, but I’m avoiding it.

I’ve said these things before, and they didn’t go through then, so I am accepting that I am not the one who can change your mind.

***

As we travel south down I-5, the landscape shifts from mountains dotted with flocks of sheep to rolling hills dotted with herds of cows. I gawk because it’s the greenest I have ever seen these stretches, when I am used to expecting brown and dusty and dry.

The grass is almost neon colored. Jen says it’s the vibrancy of new growth. California got a lot a lot of rain this past winter and spring. The rains led to floods and fallout, but also such sensuous lushness.

***

I met Jen soon after I moved to Corvallis, because I was working for her as a teaching artist when she worked at The Arts Center. We became closer friends through the renegade community art space I co-ran out of my living room(s) in the house dubbed Mt Caz. She was always one of our most ardent supporters, could always be counted on to show up when she RSVP’d yes to events, and was always talking us up to newbies in town looking for arts community.

Whenever I’m in conversation with Jen, we nearly always end up talking about the arts community in Corvallis. Our energy fluctuates between excitement, acceptance, burnout, and cynicism around ‘the way things are’ in the small college town.

As Jen and Rick ask me about my Healing Pilgrimage, I tell them that it’s partly reconnaissance for moving away. I share my nutshell takes that have taken me 3+ years to be able to voice aloud: that it’s not just the whiteness, but the homogeneity of a place with a majority that bothers me.

I share that my nervous system is shot.

I say something that I’ve said to a few other friends: that in Oregon, my take on the world is filtered through a lens of race that’s so sharp, that I just want to be in a place where that lens can soften. Where I can soften.

I also share that I was working with/for a predominately-white team in a remote non-profit job, when pandemic and BLM uprisings hit in 2020, which forced reckonings across many liberal spaces. My needs weren’t getting met and I wasn’t able to show up as my full self in a PWI workplace, and/but my strategy was to educate my white co-workers in DEI+, so that they would get it enough to see the validity and worth of accommodating my needs, to then change their ways. This is 1) a recipe for burnout, 2) the traps that a lot of DEI work falls into, and 3) a valid strategy that I was patterned into believing to be my best bet because I was trained as a woman, a design researcher, an educator, an Asian-American, an empath with community building skills, etc. etc.11

Jen resonates with the burnout. She has poured so much of her energy and commitment and time and work and optimism and analysis and belief into the arts institutions and artist communities in the region. I hear a lot of wisdom in the cynicism that has crept into her tone more and more over these last years about what may or may not change in the institutions and current power structures.

It’s a paradox: where do you accept what won’t change, and where do you hold hope and try and believe anyway? How do we be more strategic about where change is possible, and more rigorous around protecting our own boundaries about when to give of our time and energy?

The powers-that-be certainly benefit from us pouring our time and energy into systems that won’t actually change. Lip service to change and minor reform or symptom alleviation all serve to reinforce the status quo without shifting power — and is extractive of the emotional labor of (often) women of color.

Jen is also planning a move away from Corvallis at some point.

I am surprised to hear this because she is such a mainstay for this community.

I am delighted to hear this because she is a treasure and deserves the world, more than what this community can give or appreciate.

***

Reasons to share (an incomplete list)

The relief of hearing someone else describe something you yourself have experienced but that no one talks about.

To break the cycle of ‘no one talks about it’.

Because I choose to.

Because I have the words now.

***

In 2020 (as part of my scrambling self-study to soothe my nervous system and to understand what the fuck was going on with me), I participated in a series called BIPOC Surviving PWI’s from ArtEquity. It was super powerful, super sweet, super exactly what I needed at the time.

Because “you can’t self-care your way out of racism” (as Ginger Klee said), one session of the four-part series was dedicated to assessing your choices around leaving predominately-white institutions.

The panelist Lauren E. Turner described her enslaved ancestors’ escape plans as inspiration for what to consider when leaving:

When you leave is incredibly important.

Be prepared: Gather necessary resources to make it (all the way) to freedom land.

Map your destination; Know your routes.

Engage your kinship networks and support systems. You’re not going to do this alone.

In 2020, I made a commitment to myself to divest from predominately-white institutions. I know that it’s deep in my bones because some of the ways this has been playing out have not only been unexpected but also hugely inconvenient — including my slow divestment from the state of Oregon.

***

As we drive across the Bay Bridge and start to see glimpses of the city across the water, Jen shares memories of living with her grandma in the Excelsior District for a season of nonprofit work. Her nostalgia for the city. Her hot takes on San Jose, where she spent time growing up, where her family still lives now.

When they drop me off, double-parking on Capp Street in the Mission District, emergency blinkers flashing, I give her a hug and do the combo apology-gratitude thing of sorry-thank you for taking the extra time to weather the inner-city traffic to drop me off at my door. She reassures me that it is a welcome excuse to be in the city again, since she usually bypasses it completely on her way south.

The places that can stir up memories and reflections of who we were/are/can be are reminders of our multi-faceted expansiveness.

The further I am from Oregon, the more the fog lifts.12 There is a spell to living in day-to-day Oregon that makes it hard(er) for me to say these words. The longer and farther I am out of that particular bubble, the more I can try. To say. These things. Imperfectly. In progress. Experiences. Stories. My truths. My takes.

And the more I can remember who I am, the more I can bring my whole self wherever I go — including all the things she has to say — even the times I’m in Oregon.

Thank you for reading this meaty one! I <3 footnotes. Last week’s bonus included two photo essays on the layer cake of time from the Oregon coast. Next week’s bonus will be a resiliency playlist. 🎵

April 8th was the first puzzle piece to fall into place for my Healing Pilgrimage: the departure date on which I could hang the rest of my logistical asks. Thanks, Jen! <3

The short story is later adapted into an episode of the television series American Playhouse called “Displaced Person” in 1985, if you, like me, are wondering what D.P. stands for.

In Stamped from the Beginning, Ibram X. Kendi addresses both assimilationist and segregationist ideas as racism. In Covering, Kenji Yoshino maps conversion, passing, and covering as the progression of oppressive demands against marginalized groups as rights are gained over time. Both passing and covering are forms of assimilation demands.

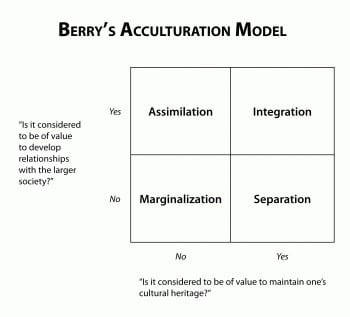

Above is JW Berry’s model, which presumes acculturation is desirable and therefore a little suspect. I include it here because it speaks to the different resiliencies that are learned depending on which milieu one is immersed in for immigrant survival/adaptation into American culture. I also learned about acculturative stress from ArtEquity panelist Ginger Klee during their “BIPOC Surviving PWI” series.

And then the next three times you talk to them, they still ask how Portland is treating you.

This is not unique to Oregon. I’m in an online Asian American sangha where we rarely go a full share without someone bringing up racism perpetuated by white people.

This is Tada Hozumi’s archived article on cultural somatic contexts. Just take with grains of salt and put asterisks on it (heck put asterisks on any of the links/resources I’m including as just one perspective informed by whatever background training and industrial complex that person stewed in). Hozumi himself has a preface on it. But I remember when I first encountered these concepts in 2020, feeling validated about the efforts and labor I was overextending myself toward translating parts of my experience into english language that wasn’t being seen/received/understood in ways that perplexed me. ((OMG if you also fall down the Lunmu rabbithole while you are on his site, let’s chat!))

See “Right to comfort & fear of conflict” as one of the Characteristics of White Supremacy Culture by Tema Okun, Kenneth Jones, et al. (They have updated their website and book since I referenced it a lot a lot back in 2020. I appreciate the added lenses of context and complexity, including a call towards racial equity principles, and a warning against weaponizing lists like this as a misguided attempt at accountability — which past me was guilty of.)

See Édouard Glissant’s “For Opacity” in Poetics of Relation.

See “The Poetics and Politics of Refraction,” a series by Jennifer S. Cheng.

See Fanny Howe on bewilderment.

See lessons from the section entitled “Refuse” from Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals.

See The Undercommons by Stefano Harney & Fred Moten.

Get lost in accompanied fugitivity with Bayo Akomolafe. (His interview with Prentis Hemphill on Finding Our Way is one starting point.)

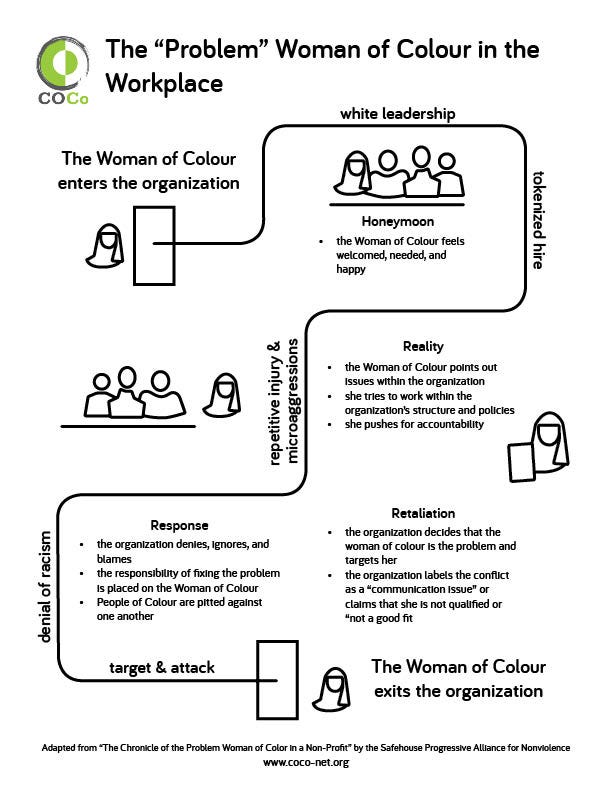

This graphic about the “problem” woman of colour in non-profit organizations was not exactly my journey but oof does it resonate. And is a good reflection tool for accountability within organizations, wherever/whenever you hold power.

Ironically, given Karl the Fog’s presence in the Bay Area.

PS Many of the above book links are affiliate links through bookshop.org, where any book purchase will contribute some pennies to support my research and writing. I also love the library and trust your knowledge of the Dewey Decimal System to get you what you need in those locations!