Welcome to Wandering Grace. I will be sharing essays exploring the themes of place and (be)longing every other Thursday, and sometimes bonus snapshots from the road on Sundays in-between. Read more about the project here. See an archived list of essays in-order here. Please subscribe or spread the word to support this project.

Last essay, we were juggling too many bags before hopping onto a shuttle bus into Sonoma County toward a contemporary agrarian residency at Bellweather, head full of memories of the fire training which we had participated in on this same land in Nov 2022.

Bellweather does not show up on Google Maps.

It’s north of Cazaderos, due east of Sea Ranch, on Kashia Pomo territory in the mountains, at the end of a long rocky driveway with cattle gates and no postal service.

For retreats and workshops, the directions that the hosts send are long, with lots of bolded and underlined text to make sure you realize that you won’t be able to rely on your pocket computer…

Load the pin on your phone BEFORE departing — no cell service along most of the drive.

…to make sure you take the time to dust off those wayfinding skills that you’ve outsourced to technology out of habit,

Once on the driveway, stop following the pin and instead follow the signs.

…to make sure you understand the necessity of entering a different headspace and orienting to a different way of life before coming here.

Before you head to the land and when you arrive, please take a safety vow. This is for your energetic protection especially because the land is not an easy place and is way tf out here! We want to make sure you are prayed up and protected so you receive the most beautiful experience! We ask that you be mindful and careful throughout your stay here. We are very remote and decisions made without discernment or wisdom can be costly. If a trail feels like an edge, or you’re doing something that feels a bit dangerous, just don’t do it! It ain’t worth it!

The nearest town and grocery store is about an hour’s drive away.

The nearest emergency room is over an hour’s drive away.

The land stewards Jiordi and brontë have a membership with AirMedCare Helicopter services, and part of orientation to the land is knowing how to get to that field for emergency evacuation via airlift if anything should happen (pray that nothing happens).

The drive up to Bellweather includes traversing three cattle gates as you travel through other people’s property. You park the car and jump out to open the gate, drive a few feet to the other side, and then put the car in park again to walk back and close the gate. It is a neighborly act. It is an embodied ritual that helps you enter a portal of remote rural life.

We pack our groceries in. They pack our trash out. There is no trash service up here in the mountains.

Don’t leave your junk or excess baggage up here; there won’t be anyone here to help you carry it or to process it.

But you can leave your shit here, in the composting toilet, for the benefit of the land.

***

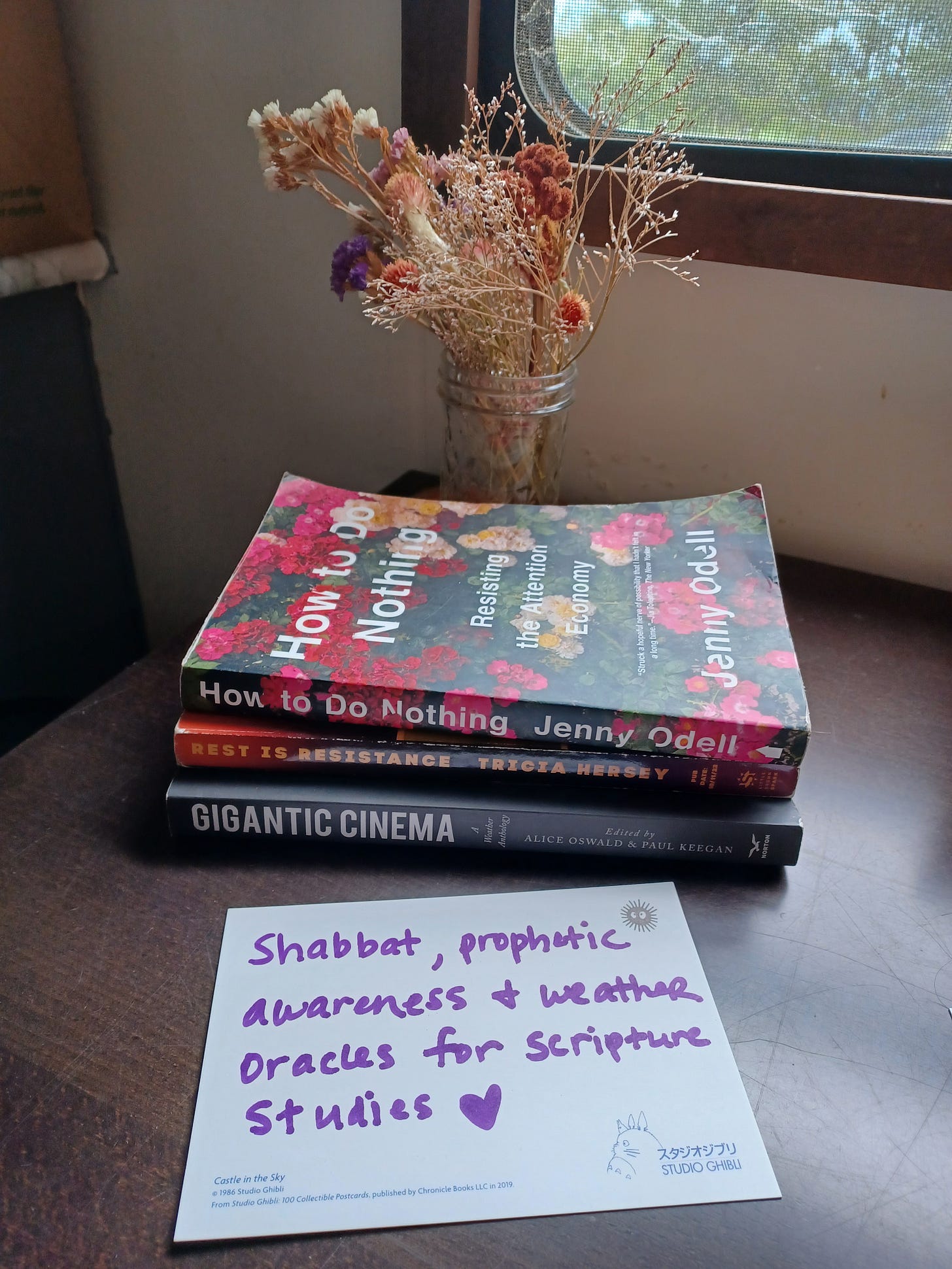

“Resistance is a spiritual practice and a practical map. We learn how to make a way by building as we go. We resist by crafting ease and invention. We resist by reclaiming autonomy and leisure. We remain flexible and ready to shapeshift as our bodies call for rest. My offering to you as a main point of how to resist always goes back to the brilliance of the maroons of North America. Living and thriving within two worlds, they built safe spaces. Crafted an alternative place of freedom miles away from the plantations and sometimes right in its backyard in the deep bush, hidden in plain sight while tucked away.”

-Tricia Hersey, Rest is Resistance

Have you experienced an ‘alternative place of freedom’? A place that embraces fugitivity? A place where you remember that other ways of being are not only possible, but natural?

I’m not sure how to write about such places, because sometimes they don’t want to be public. They want to remain under the radar for a reason.

My time (t)here feels more an ongoing relationship with people and place than a defined trip with beginning and end. The land resists easy lessons, or even meandering ones like the closure my essay-writing strives for here.

***

Bellweather is beautiful and alluring.

Once on the land, silence is easier. Prayer comes more easily. Time slows down.

Modernity falls away — squatting to pee on the land, you are in intimate relationship with weather and her forces and her whims.

Work sorts itself more effortlessly. It takes more energy to force myself to do anything that isn’t necessary or nourishing. Bullshit jobs reveal themselves to be just so — remote work is harder up here.

Tending to the needs of the land, or to the animals, or to the building of infrastructure that makes life possible feels more urgent and more needful. It feels good to be able to take part in any of these collective efforts: helping to wrangle the alpaca from the barn into the fenced paddock without losing any of the goats at the same time, putting seedlings into the ground, holding up the barn door while they do some sketchy maneuvers with a skid steer to try and get it onto its rail. I feel relief that I at least have some gardening experience, so feel confident contributing to the digging and planting and watering-in of tomato and onion seedlings.

During my two-week ‘contemplative agrarian residency’ at Bellweather, I’m constantly looking for ways I can help, but mostly I try to stay out of the way.

After all, I’m just an awkward city mouse in the country for retreat. It’s easy for city mouses to bumble up country mouses’ projects. I grew up and spent the first three decades of my life in big cities of 1mil+. For the last handful of years, I have been living in a smaller town of 60,000 people, which might seem country to big city folk, but is still a connected college town and not even the ‘one-street downtown’ kind of small-town that also sometimes counts for rural.

I’m using these facts as shorthand, but what I also mean about me in particular is that: I didn’t grow up in relationship to land in a way where I learned the attentional or physical skills required to tend to an ecology; I didn’t grow up around power tools so didn’t absorb an ethos that we could build what we need; I barely grew up around pets or babies who required rhythms of creativity and care, maintenance work, relational reproductive labor.

Part of being here is me grappling with: what am I desiring or willing to do to change any of that, given the healing and re-connecting and de-colonizing work that is part of our time’s yearning and mandate?

***

Everything here on the land is slow and takes longer than one would imagine — sometimes frustratingly so. Efficiency — particularly capitalism-fueled efficiency — is a piece of city life that doesn’t make it up these mountain.

Reading poetry and walking the land and devotional attention to the world come more easily, though. It is a sign that I am still in the (un)learning cycle of (re)valuing my work in the world as a poet and as a writer and as a quiet person paying attention to the world, that I spend a good portion of my retreat feeling guilty about not doing more, of not contributing labor that might ease the logistical burdens of my hosts…even though I am here on a contemplative residency, where my work is to…be.

The concept of rest proves elusive when I feel so guilty for indulging my own rest in proximity to hosts who seem like they can’t get enough for themselves.

***

Residencies and retreats are portals. The rhythms of your days and attentions, suddenly shifted to a different kind of time, give you insight into your day-to-day defaults.

On this land, the silences invite a deepening exhale.

On this land, the silences invite more silences, a different kind of attention, a different kind of pace.

Here, the needs to tend to bodily functions focuses the mind and reveal the absurdities of modernity — drawing you closer to the primal basics of both taking care of yourself (self-sufficiency) and accepting collective care (interdependence…or as jiordi calls it “radical co-dependence”).

Being on this land in this way makes me question previously taken-for-granted rhythms and routines: Do you really need daily showers? What is your relationship to dust? How much heat do you need?

What is enough, and what is excess?

How do we stay human in our current world — what do we choose to adapt / adopt / forgo / sacrifice without too much hardship and with pleasure? And which luxuries do we bring with us because delight and nourishment fuel our work, embolden our risktaking in other arenas, and meet us exactly where we’re at in this moment in time?

***

“Creature comforts” acknowledges that we are still creatures.

***

My modern monkey brainchatter persists, but here I can seed the questions into the mud of my mind,1 and into the mud on the grounds. Questions of: How do I live my call in ways that are well-resourced and that serve the world well? Questions of: Are all the parts of me ready for this transition? Is every one of my bodies actually ready to move away from Oregon?

Here, I realize that the stored trauma energy of 2020 and Oregon and break-ups will release slowly (and quickly) over time, in different places, in different ways.

***

There is one weekend where I will be on the land on my own without a car because the main caretakers are going into town for a wedding.

Mostly, I am looking forward to it. My biggest consideration is whether I want to be offline for this extra-solo retreat time — how I want to be in relationship to texting or calling friends, whether I want to be on Netflix and YouTube during this weekend.2

There is a meditation I think about often where Allison Jones guides the listener to actively sever the energetic tethers that pull oneself toward another person, or to a task on a to-do list, or into social media platforms, or toward pieces of technology encountered throughout the day. To let those severed connections float off into space, to bring all of that energy back into oneself.

It’s not until dusk, when I’m standing in the garage looking out at the medley of vehicles and trailers, and the trees silhouetted against sky, clouds threatening rain, that I realize that I will be the only human being for miles and miles and miles, on this entire patch of 365 acres.

This kind of “alone” is different than solitude in my room in a house in the city. This kind of “alone” is different even than a retreat in the woods, or camping in a national park. Yes, there are tree beings on this land and the animals — chickens and goats and Simone the cat — to keep me company, but there are no other humans here. That kind of existential terror gets at my caveman brain.

My whole body starts trembling uncontrollably.

***

That weekend, I get two texts that confuse me. One is from the housemate where I was staying in Albany, CA, sharing that she has a friend coming over and asking if I want to join them for a movie night, which does not compute since I am two hours and three cattle gates away without a car. Did I forget to tell her goodbye when I was leaving? Did she send me the text by accident? Was it meant for someone else?

Another is from a friend checking in because he can’t find Bellweather on the map. At some point, he sends a text saying, “Haha. I will go there if i dont hear from you. Today i was at the vet and when filling out the form for the emergency contact entry, i got inspired to switch it up each time i have a chance and let that new person know. I know i feel important when someone puts me down as an emergency contact…” I am convinced that this is also a mistake — a text set to the wrong channel, meant for a friend he was planning on meeting up with downtown, me eavesdropping on a conversation that they were continuing on about pets and emergency contacts.

Upon waking at 5 am the next morning, I realize that those texts actually were meant for me — that my friend was saying that if I go missing up here in the mountains, he’d come looking for me.

I am amazed by how thoroughly convinced I was that I couldn’t be the ‘you’ in question. I am unsettled by how quickly my ‘I’ had become untethered from others, so that I couldn’t even conjure a possibility where I was the intended recipient of their consideration.3

“A person (or a thing) comes to exist by being met in the most authentic way by another…How close this is to Rilke’s declaration that our greatest summons is really to see the things of this world. We are because we are seen; we are because we are loved. The world is because it is beheld and loved into being. On a silent retreat, while watching a line of ants traveling up a hillside, words came to me that I would repeat again and again in my mind: I am in the world to love the world.”

~preface by Anita Barrows to Rilke’s Book of Hours

***

Near the end of my residency at Bellweather, there is a small group of 5 of us who go down to the pond to remove the azolla, an aquatic fern which has overgrown and obscured the surface. Azolla, which is a pest to the pond’s ecosystem, but which when harvested, can be turned into nutrient-rich fertilizer.4

There’s a whole operation, this year with row boats and skimmers, new equipment purchased from hard lessons learned during last year’s ordeal. Jiordi is singing and clowning the whole time — buoyed by the fact that this is a collective effort instead of his typical solo duties on this land. The bullfrogs are hilarious because they sound so rumbly and serious when they’re croaking, but when startled they dive into the water with a high-pitched squeak. brontë records bird song on their phone.

It is a sunny day, it is sweaty work, it is fulfilling.

***

There’s something here: Not that we have to ‘earn’ our rest through our labor, but that when we are in rhythms of caretaking and creativity,5 rest can be more restorative even as it is more fleeting, and even when it comes as a surprise. The land we take care of takes care of us back. Relationship reciprocated.

***

On my last day at Bellweather, I decide I want to take an “after” photo of the pond post-Azolla-removal.

I snap some photos from up high on the ridge — the same position where we witnessed the first hillside burns of our fire training.

The water calls me to come down. I end up on the dock.

The water calls me into her embrace. I strip and jump in.

I turn to float on my back, and the moment the buoyancy cradles my neck in rest, I gasp aloud at receiving the embodied message of: you’ll be okay.

Because I had drawn this moment before. In a piece I had made last year called “The Body of Water That Is You” about the healing cycles of nature, and how bodies of water will mother you through the life and death of your mothers.

Still you — through the transitions, through the losses, through the changes, through the everything. Still you. All those questions planted in the mud — of where you will live and who you will be and how you will serve…I don’t leave here with any answers. Just this feeling, an embodied message of love, of you got this and we got your back.

Next week in Migration Tour timeline is Mother’s Day, which we will spend in the company of mothers and sheep back in town.

Kaira Jewel Lingo, in the tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh, invites us to: “Without trying to figure out an answer or solution, see it as a seed that you can entrust to the soil of your mind. Let it lay there peacefully and quietly. Let yourself rest back into the unknown of this moment… see if you can let your body surrender to this uncertainty.”

I did end up tuning into some of this annual 24-hour event called Reveil where we follow the sunrise around the globe via broadcasting “streamers at listening points around the earth”…which makes you appreciate how big the Pacific Ocean is when all the commotion of our west coast dies down for hours on end until you reach landfall again in Asia. (h/t Neil Brideau and Fereshteh Toosi!)

I also realize how careless I’ve been in not sharing my full Migration Tour itinerary with anyone. I had friends who were following along for various bits and pieces of my trip. But it’s easy to slip through the cracks as a solo person without parents or life partner tracking her whereabouts. Later, I will end up putting together a spreadsheet of addresses, dates, and host locations for Southern California — and sharing the document with a few trusted friends “in case of emergency.”

I have been thinking about ‘rhythms of caretaking and creativity’ ever since spending time with Jenn and her family.